Communications Manager

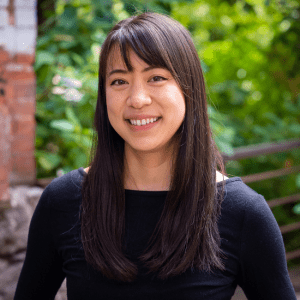

Catherine Nguyen, founder of Mora Mora Farm

The fourth interviewee in this series about Asian American agriculture is Catherine Nguyen. The daughter of Vietnamese immigrants, Catherine pursued farming out of interest after studying human nutrition and as a way of exploring farms across the country. In 2018, Catherine founded Mora Mora Farm and now farms out of Troutdale, Ore., providing local produce to her Community Supported Agriculture membership.

All photos were taken by Emilie Chen, unless stated.

Catherine Nguyen became interested in farming after studying human nutrition during college. Though her parents, who arrived to the US in the 1980s from Vietnam, worried about her pursuit of the labor-intensive career, Catherine found farming to be both fulfilling and a means of exploring the vast United States.

After interning on farms in Colorado and Washington, she moved to Portland, Ore. In 2018, she founded Mora Mora Farm as a beginning farm through East Multnomah Soil & Water Conservation District’s incubator program. After completing the five-year program, Catherine began to farm on leased land in Troutdale, Ore., including from Pam Oja, who was featured earlier in this series. Most recently, Catherine has been farming on one-and-a-half acres on a private property, where we held this interview in the fall of 2023, just as she was preparing to take a one-year sabbatical for 2024.

“Can you explain what Mora Mora means?” I asked.

“Slow. Slowly,” Catherine replied.

“How is that expressed in your farming style?”

“I don’t know if it’s currently expressed,” she pondered. “I feel like when I chose that name, it was with the idea that if I didn’t get a handle on this concept, then I wouldn’t be successful in the farm and in life. So it acts more as a reminder to me to slow down, than as something that the farm currently encapsulates.”

“You’re taking a sabbatical in 2024. A sabbatical feels like an expression of that.”

“Yeah, I’m trying to be pretty disciplined in rest, [with] the amount of decisions you have to make on a day-to-day and how quickly you have to respond and move as an operation when your product is perishable,” she replied.

A huge factor in Catherine’s decision to take a full year off in 2024 was the discovery that an old sports injury from her college years would require surgery.

“I feel like the tractor work is what’s strenuous for my body the most,” Catherine continued. Farming is undoubtedly quite physical because of the actual farm work, but as she emphasized, farming is also very mental and emotional. “When your livelihood depends on the weather, we’re watching it like a hawk and tuned into things like rainfall or early heat… [In 2023], we had a pretty ideal weather year. Every season was as it should have been. 2023 was my best year. 2022 was my worst year, and the only difference was the weather.”

Catherine harvests pink daikon.

“Is there anything that you would say makes your farming style unique?”

“For this area, I feel like the size of it is really unique,” Catherine reflected. “There’s a lot of farms that are sub-one acre, or they’re like, five-plus acres. So to be a one- and-a-half acre size and to do it solo, I think is unique. I also tend toward more of the minimal tillage, no-till type of system. I really like the kind of human-scale, hand-tool size operation. It is brutal on your body, but I also like how close you can be with the soil. I feel like if I were on a tractor everyday, I would lose a little bit of connection with what I was doing.”

Given that most of my interviewees so far had ancestral roots to farming, I asked her: “Is there anyone in your family who works in farming or food in some way?”

“No, not that I know of. Both my siblings are engineers. My mom has worked at the post office for as long as I can remember. And my dad has worked in that computer software field for as long as I know,” Catherine replied, though she later discovered that her father temporarily worked on his aunt’s sugarcane farm in his youth.

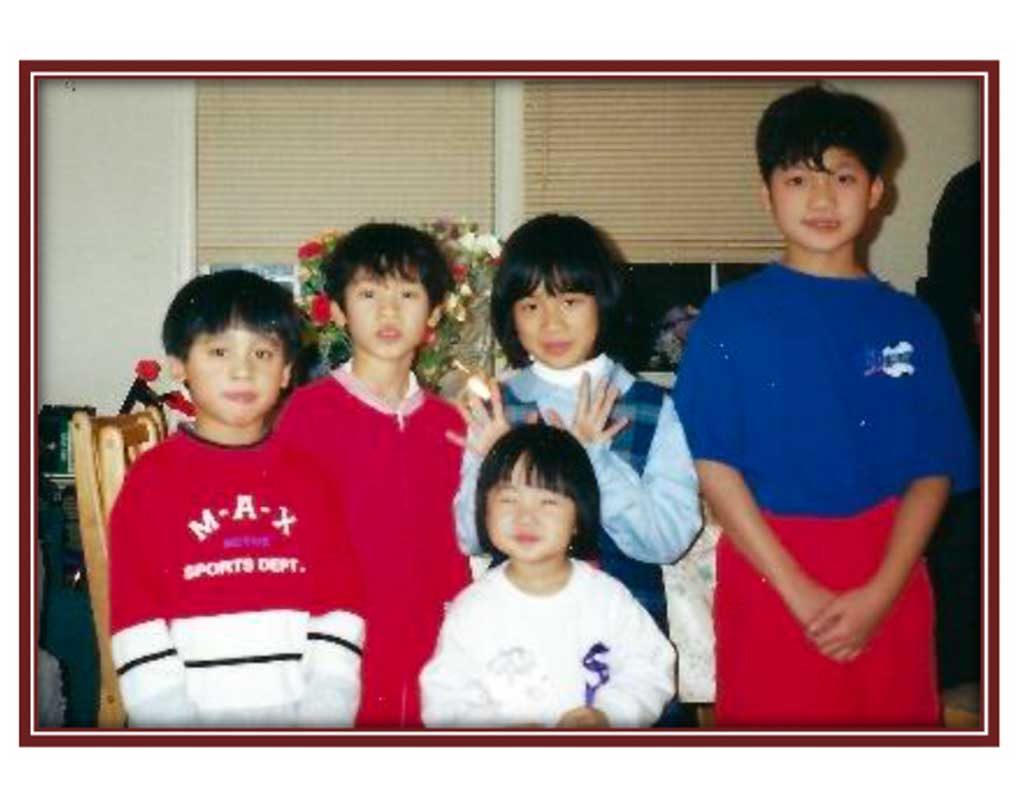

Catherine with her siblings and cousins. Photo courtesy of Catherine Nguyen.

“Do you mind if I ask what your family’s response has been to your farming?”

“I think it’s one of those things they don’t quite understand, and I know that I don’t understand them. We both just come from wildly different cultures where career plays different roles, farming has different connotations, and the opportunities surrounding both are just different.”

I felt an ease and familiarity talking with Catherine about the challenge of forging a career pathway in something that immigrant parents may neither understand nor support. From my own experiences growing up in a predominantly Asian immigrant community, I know that many of our immigrant parents have come from agricultural economies, where they dreamed of anything but manual labor for their children. But Catherine’s passion for farming is clearly visible to those who have worked with her.

She shared, “I remember when I was working up in Snohomish in 2017. They all came up and visited, and that was the first time they saw this type of farming. My dad went up to my boss and was like, ‘So I don’t understand. Why do you do this? Why are you farming?’

“And all my boss said was, ‘Just let her do it. She’s good at it.’

“I think it’s just one of those things where, coming from their history, [my parents] want stability for their kids. And farming is the last job that offers stability. I imagine that it’s all toil when it comes to anyone’s perception of farming. … I think that my cousin’s video [about my farm] actually did a lot to change their perception.”

“Do you know how your parents got to Virginia?” I asked.

At the time of our interview, Catherine admitted, “I wish I knew more of my parents’ history when they were back in Vietnam. … I know my dad and all his siblings were in the war. … Yeah, we have yet to delve into that as a family.”

She shared a few bits that she knew of her parents’ experiences, and I was reminded that the trauma her family experienced while fleeing Vietnam is not uncommon. A qualitative study has found that “second-generation Vietnamese Americans and their parents experienced uncertainty and avoidance to discuss Vietnam War-related experiences.” Similarly, Catherine does not know what livelihoods or occupations her forebears previously had in Vietnam. “Many of my aunts and uncles were in their late teens or early 20s during the fall [of Saigon]. I don’t know if they ever got a chance at a career, like we know it in the West.”

But during her sabbatical in 2024, Catherine visited her extended family in Vietnam, providing opportunities to learn more about her family history.

After returning from her trip, she shared: “It was my first time going to Vietnam, and I feel so lucky to have gone with so many cousins and aunts and uncles. I visited old family plots and graves, met new cousins, and just learned a lot about my family’s history and culture. My dad fled Vietnam after the fall of Saigon. He was at sea for 17 days before landing at a refugee camp on an island in Malaysia. I’m still not sure how, but he ended up in America in July of 1981. Went to school, got a job, started sending money back to his siblings. He was one of ten siblings, and all except one were still back in Vietnam. My paternal grandfather and brothers were sent to re-education camps, and all my aunts recall this as a particularly rough time.”

I asked Catherine if her curiosity about her family’s history resulted in her farm becoming a pathway to connect to her culture.

“That is a complicated and interesting question,” she replied thoughtfully. “When I first started farming, I stuck to what I knew would sell in this area. It’s a lot of Western crops that I’m more familiar with, like carrots, kale, all that stuff. As 2020 hit and everyone was talking about race, I started to think more about my heritage and history. From a business side, more markets were opening up because of those conversations. I was getting more interest from Asian families asking about specific crops, when I had never gotten those questions in the first 3-4 years of farming. So I was like, ‘Okay, there’s a place for me to explore myself in this and still support my livelihood.”‘

“In the current state that the farm is in now, the crops that I choose have to have a little bit of intrigue for me, and they have to make financial sense. …for some of the Asian restaurants that have reached out or if there were members in my [Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)] who were looking for specific crops, I’ll grow one or two of them. I don’t know if I would ever have an Asian crop CSA… It’s still one of those things, as a business … it still needs to pay the bills, and I am just not sure there’s a stable enough market for it yet.”

“A lot of the crops that I want to grow, that are more familiar to Asian families, need more heat than I have [here in the Pacific Northwest]. There’s a world in which I get a greenhouse, but it’s hard from a market standpoint because [these crops don’t] have the demand that allows me to charge a higher price, and I need the higher price to support the infrastructure for growing the crop,” she added.

Pink radicchio is a unique offering that Catherine offers her restaurant accounts and CSA membership.

A sampling of the fall vegetables received by Mora Mora Farm’s CSA membership.

The common thread in all my conversations with farmers in this series has been the economic pressure of sustaining a farm business. In 2023, Catherine was able to obtain two grants from Portland-area nonprofits, Growing Gardens and Oregon Food Bank, which allowed her to grow food for other nonprofit organizations such as Refugee Care Collective. The grants supplied half of her income for the year, enabling values-aligned work that supports local food access, but she expressed uncertainty for future years where windfall grants may not be available. The other half of her 2023 income came from restaurants and her CSA membership. It goes without saying that farming requires discipline and grit for hard work.

“During peak season in 2023, what were your hours in a day? And how many days a week were you working?” I asked.

“I was working probably like six or seven days a week, depending on what was going on. I had a funky schedule [in 2023], because I realized working in peak heat isn’t ideal.” From July through August, she said, “I would work a 5-to-12 shift and then take a four-hour break and then come back to the farm from 4 until 8 or 9 ‘o clock. …Once September hits, it slows down a bit.”

Catherine examines her fall season collards.

“What are some challenges you’ve had to overcome?”

“There were definitely tears in my first year,” she confessed. “I remember that first year just being brutal. …But since then, I’ve come to understand soil a little bit more… understanding the ways that you can make it healthier and more productive… Honestly, having Jen Aron in this area is an amazing resource. She spearheaded the more recent, low-/no-till, smaller scale movement [in this area] and understanding about soil biology that I think a lot of us are lacking, because we grew up in more chemical-based farming.”

“And what have been your most rewarding moments of 2023?”

“Good question!” Catherine mused. “I never thought I would be the person to answer with this answer, but this is my true answer: It was the best financial year of the season. And it felt like an achievement, because this is the first year where I was like, ‘I do think that it’s possible to farm and make a decent livelihood from it.’

“What are you looking forward to in 2025, after returning from your sabbatical?”

“In 2025, I am hoping that my pace of work will be chiller,” Catherine reflected. “I feel like as I grow as a farmer, there are moments when I catch myself freaking out about something, not because it’s actually an issue, but because I’ve made it a habit of freaking out about it. I still come into harvest days frantic, because that was my experience of harvest days when I was an intern. It is stressful, when you’re trying to get plants out of the sun before they wilt. But there were moments [in 2023] I had to remind myself, ‘I’m up early, I got this. It’s going to take this amount of time. I know that I can do that at this rate.’ I’m relearning the habits that aren’t helpful to me in the long run. So I’m hoping to come back to 2025 with a more settled disposition.”

BLOG

Inspired by the historical contributions of Asian farmers along the West Coast, Communications Manager Emilie Chen explores Asian American farming identity through five interviews.

BLOG

In the third interview of a series about Asian American farming, Emilie Chen speaks with Malia Myers, co-founder of Landmass Wines based in Cascade Locks, Ore. Malia shares her journey into winemaking and the inspirations she has drawn from her great-grandparents, who were Filipinx immigrant plantation workers in Hawai’i.