Communications Manager

Senior Communications Manager

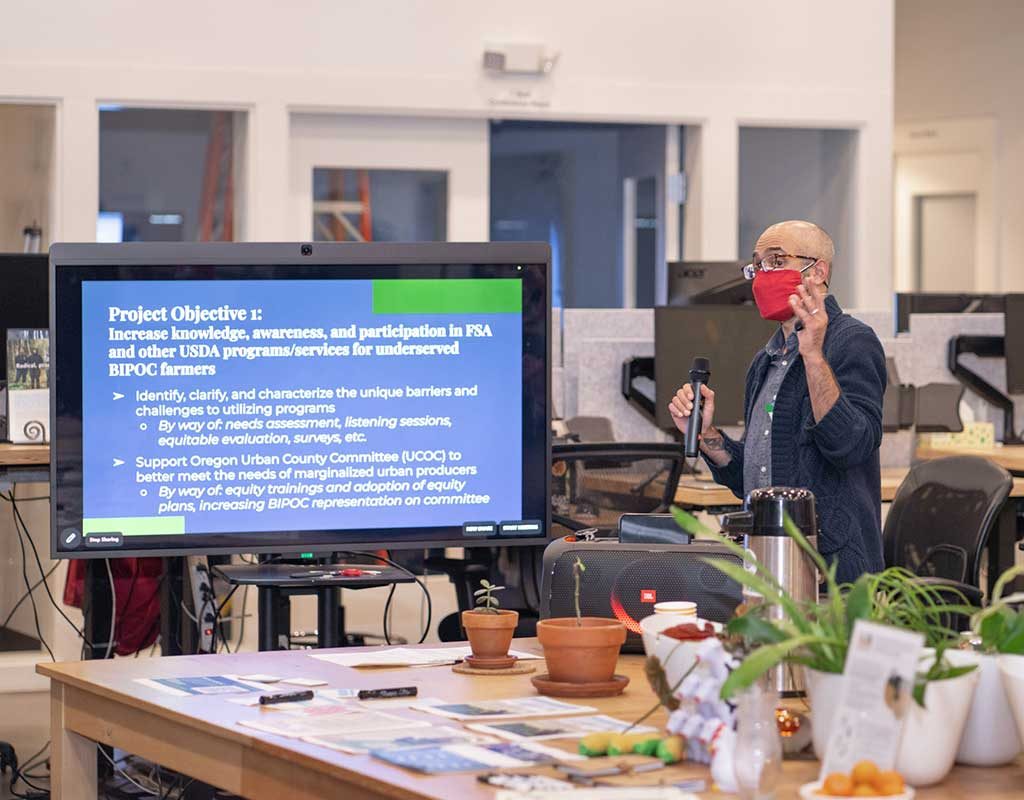

Eric Rodriguez. Photo credit: Emilie Chen

In a conversation with Emilie Chen, Eric Rodriguez shares perspectives on urban agriculture, community-centered programming, and what he’s looking forward to in his new role.

How has being from New York City shaped your perspectives around urban agriculture?

I moved to Portland about two years ago, and one of the things I’ve been thinking about is what urban agriculture means here. I definitely had one perspective of it based on my experience in New York City, which doesn’t necessarily apply here.

Outdoor space is so limited in New York, and land is more valuable than buildings. Developers will knock a building down just to sell the land. Urban agriculture oftentimes takes the form of community gardens, or people dumping compost on a parking lot, or people zip-tying containers to their fire escapes.

“

A lot of my [perspectives have been] shaped by people who were doing things “by any means necessary.” No one was doing it specifically to become a farmer. They were doing it because they were trying to provide food for themselves and their communities, and they had full lives outside of that. The strongest and most visible projects were historically in areas that were primarily Black and Brown, [where there is a history of] disinvestment and redlining.

My understanding of urban agriculture from New York is shifting in a lot of ways. Urban agriculture, depending on where you are, can mean very different things to very different people. There’s no clear-cut approach; the definitions are really based in centering the communities who are doing that work, which also gets to the heart of the equity work as well.

Eric speaks to the attendees of the Winter Farmers Welcome, held at the Ecotrust office. Photo credit: Dreshad Williams via FLI Social

I have had a professional career of very serious hobbies. They’ve all been, I think, part of the same focus: equity work, green spaces, food access, plant life, all the things.

My last job in New York was in professional horticulture. I was the director of horticulture for the High Line, which is a big urban reuse park. I’ve built urban farms and community seed libraries with public housing agencies. I worked at a historic house museum, which had a Green Schools program, and an integrated community library. I’ve also been a policy wonk, writing policy papers and doing policy analysis on various city things. I worked as a housing organizer for a while.

One of the things I was trying to do [as a policy analyst] was map social phenomena. I really love maps and infographics and visuals. It works for my brain. I was working on mapping recidivism in various neighborhoods in New York City and then trying to not do deficit model storytelling. Instead, I was trying to find out where local libraries were or how far people’s closest green space was. That took hanging out with community gardeners, being outside and sharing food with them. And I thought, “You know, I really enjoy being outside a lot more than I enjoy sitting behind a computer.”

So I applied to be a horticulture intern full time at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. I spent eight months living, breathing, dreaming, sleeping plants. In all of that, I was very interested in food pathways, native plants as food, indigenous foods. I did a capstone project about scaling small Brooklyn backyards for edible native plants. To me, that’s how I could bridge the gap between formal horticulture and urban agriculture, which is its own form of horticulture, its own complicated histories.

Now, growing plants, attracting butterflies, bringing people together and creating community and support networks and systems for each other, advocating for redistribution of wealth and resources to marginalized communities—it’s all kind of dovetailed.

“

Actually, I came to Portland for the first time during that internship at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. I knew the program was ending, and I was trying to figure out what the pathways were. I was looking at various master’s programs. But I had some friends who just moved here, and I visited and I really liked it.

About 2017 or 2018, my spouse and I saw Portland again and were like, “We’re gonna do this.” We were both burned out on New York stress. I wanted chickens. I wanted to have a garden. A big part of me leaving New York was I wanted to be in a place where gardens are really celebrated, not necessarily like status symbols. It also seemed like Portland has a really vibrant activist scene and nonprofit scene where people are plugged in and doing things on the ground. That really resonated with me.

One of your first jobs after moving to Portland was working with Zenger Farm. What did you learn there?

I was the director of CSA Partnerships for Health, which was basically a partnership between healthcare centers and farmers. I was sitting in the middle of those relationships, basically making the case for why CSA [Community Supported Agriculture] shares should be paid for by Medicaid providers as a preventative health measure. Scientific evaluation was involved, so I was working with academics and researchers.

Working in a program where a lot of the goal was preventative care was a huge experience for me. It was really amazing to think about how you could create these services where you’re directly passing money to farmers and guaranteeing their income. I was able to pass on hundreds of thousands of dollars to regional farmers. To me, that felt like a universal win for patients, for farmers, and for activists who are interested in this kind of work and starting these programs.

Making the case for food as a basic human right and human dignity has shifted in a lot of ways. Medicaid insurers and health insurance companies have shifted to seeing that if you provide food for folks consistently, their health outcomes will change. This actually saves us money, right? It’s a very different conversation around urban agriculture from when I first started.

What spoke to you about the role of Director of Food Equity here at Ecotrust? What was that spark that compelled you to apply?

I would say the sheer span of the job description. All of the projects were really buckets of my personal interests. I love fellowships and communities of learning. And a lot of the programs at Ecotrust—not just in food equity, but as a part of the larger organization—were already on my radar.

Equity was so centered in [the job]. It’s in the title. One of the underpinnings I think about all the time is not just who has access to food, but who has access to the means of production? What is the food that people are getting? Is it specific for them? Do they see themselves in it? So much about food is a sense of home and culture and comfort. But if you don’t see yourself reflected in it—and particularly, this is a bigger issue for immigrant communities and refugee communities—how demoralizing and terrible that is. For me, the question of food equity goes to the individual’s sense of home and who they are. And joy. I do think a lot about centering joy in food equity.

Eric gives a presentation on food systems work at Ecotrust. Photo credit: Dreshad Williams via FLI Social

I like being part of projects where you’re building something from its beginning, like the FSA urban agriculture cooperative. It seemed rare that you could just walk into something where the [the organization says], “We have the funding, the networks, all of this. Just make it go. We can design something collectively.” That was super exciting for me. I’m really excited to put together informational documents that streamline all of these complex governmental programs. I really like taking information and making it simple. That also, to me, speaks to equity and accessibility.

I’m really excited to relaunch [the Viviane Barnett Fellowship] in whatever form it takes. I’m excited to think about ways that we can create connections between different programs we have at Ecotrust. I like designing programs where nobody ever really leaves, even if they go off and do something else, because it’s a part of this larger ecosystem of social justice.

I really appreciated Ecotrust’s perspective on indigenous food pathways, environmental care, and ecoregions. These are all things that I love, but haven’t quite found a place where all of those conversations are happening simultaneously. That felt like, “Yeah, this is a place I would love to learn more and grow.”

Project

Project

A cohort-based program designed for aspiring and experienced leaders of color working to build equitable, climate-resilient food systems