Measurement & Evaluation Manager

Feny Lim (left), chef and owner of Pasar, with Denise Chin (right), Ecotrust Measurement & Evaluation Manager, shares opening remarks at Mari Kita Makan in March 2024. Photo credit: Christine Dong

In March 2024, Mari Kita Makan was held at Pasar, an Indonesian restaurant in northeast Portland. This free-to-attend dinner event was organized by Denise Chin, Ecotrust’s Measurement & Evaluation Manager, to connect immigrants and diaspora from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore in the Portland area.

All photos were taken by Christine Dong.

Listen to Denise Chin read this story.

On a sunny spring Monday evening, over 40 attendees made their way to Pasar, Chef Feny Lim’s newest restaurant in Portland’s Alberta neighborhood. The attendees represented immigrants and diaspora from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. With the restaurant closed for service on Mondays, we had the place to ourselves, and we filled it with bright-eyed smiles and enthusiasm to connect over a feast.

The owner of Indonesian restaurants Wajan and Pasar, Chef Feny shared her experience of moving to the US as a student and then her ambitions to start a food business, beginning with a food cart. Her story of departing from the familiarity of her life in Indonesia to pursue big dreams is a story similar to mine and many others who were in the room. As the servers brought out each dish, our eyebrows shot up as we admired how much thought went into the presentation (bamboo-woven baskets lined with banana leaves); use of ingredients some had not seen in a long time (petai, or stink beans with tempeh); and the attention that went into ensuring a delightful dinner experience (the caramel–like warm, melted palm sugar that flowed out of the coconut flake-coated klepon ball—a contenting one-bite dessert to perfectly end the meal).

Urap Sayur, Indonesian-style blanched mixed vegetables seasoned with spice-toasted grated coconut.

Klepon (left), also known as ondeh-ondeh, is pandan glutinous rice and sweet potato ball with palm sugar filling, covered in grated coconut. Pulut Tai-Tai (right), also known as pulut tekan, is sticky rice with kaya, coconut custard jam.

Around the tables, guests engaged merrily. While I had prepared station activities to break the lull in conversation, the group didn’t need much to break the ice. Soon the room was buzzing from a cacophony of different topics. It didn’t take long for attendees to exchange contact information and form group chats to stay in touch.

I could hardly believe it—this community, here in Portland, of people like me, taking up space in a search to find belonging.

The menu for Mari Kita Makan.

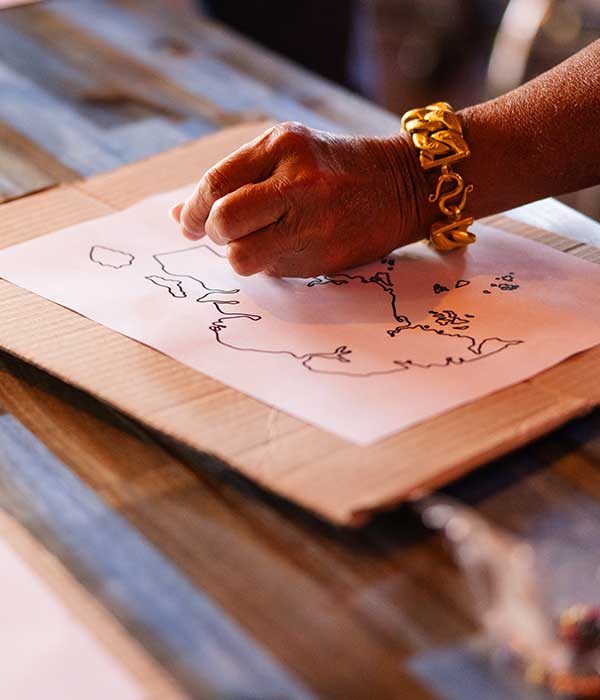

Denise prepared icebreaker activities, such as maps for attendees to mark their city of origin.

In the winter of 2010, I flew across the Pacific Ocean and descended into the rolling hills of the Palouse region, arriving in the college town of Pullman, Washington. This scenery was quite different from my bustling, populous home city of Kuala Lumpur. I connected with a small group of fellow Malaysians on the Washington State University campus and, over the years, with Malaysians in each city I lived. Our gatherings always included food. Our conversations revolved around finding ingredients at the nearest Asian grocers, our visa situations, and when we would next visit home. With our collective memory, our tongues drew words and expressions (lah!) from Malay, Cantonese, Mandarin, Hokkien, and other languages that we otherwise kept hidden outside of the group. We would end with a group photo and suggestions for the next occasion to meet again (Merdeka, Malaysia’s Independence Day; Eid al-Fitr; Chinese New Year).

I was acutely aware of Portland’s nickname as the “whitest city in the country,” when I moved to Oregon, yet I also began to notice the visible spaces for people of color. When I started at Ecotrust, I was invited to join the Black, Indigenous, and all People of Color (BIPOC) Affinity Group, a space open to only colleagues who identify as BIPOC. Here, we collectively breathe a sigh of release, nod to the similar feelings and expectations brought upon our backs, and organize when the need arises. Most importantly, we fellowship around food and share joys together, invoking similar sentiments I experienced at Malaysian gatherings. I recall laughing my hardest for the first time in Oregon at one of these meetings.

Mari Kita Makan attendees chat as they settle into the restaurant.

An affinity space is antiracist work. Affinity spaces are intentional, brave spaces for specific groups, by similar identities or racial background, to come together and exist as authentic selves outside of the white gaze. Affinity spaces can be misconceived as being exclusive, but really it is a space to share experiences, trauma, and healing that can’t always be harnessed in a mixed group. It is a place to share aspirations, cultivate community, advocate for change and show up for collective liberation.

In 2023, Ecotrust gave me the opportunity to work on a project of my design related to food systems equity. My ideas always came back to how I could help build community, regardless of how small my project might be. I thought back to my past self when I had just moved to Oregon, optimistic about my ability to adjust to another part of the US as I had done before. However, I barely came across people of color in my daily activities like grocery shopping, visiting the library, or recreating. I became aware of how different I was and noticed how I was easily overlooked. Had I found an opportunity to connect with those of similar backgrounds as me, I would have felt less lonely, more empowered to be myself, and not hide from things that made me seem different but instead, celebrate them. With that, I dreamed up Mari Kita Makan.

“

I wanted to bring visibility to this group, and I was pleasantly surprised by its magnitude.

The idea for Mari Kita Makan (“Come, Let’s Eat”) was to have an affinity group. A community dinner that would bring together the diaspora of three countries in southeast Asia with relatively small populations in Oregon, specifically Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Food is a connector, and if I know anything about my fellow Southeast Asians, it is that food would bring us together. I was so excited when Chef Feny Lim agreed to collaborate on this dinner. With great care and intention, she curated a menu that weaved similarities from our three countries and evoked nostalgia for flavors and smells not often found in Portland. With philanthropic support, we made this a free community event for our very specific audience.

Chef and restaurant owner Feny Lim shares her story to a full house of Mari Kita Makan attendees.

The night went as smoothly as I could have hoped for, despite unavoidable glitches (it was, after all, my first time planning a community event like this).

My biggest takeaway is that the community exists and is HERE! I wanted to bring visibility to this group, and I was pleasantly surprised by its magnitude. I was aware that Malaysians do have a presence in Portland, but I knew little about Indonesians and Singaporeans. From the overflowing list of interested registrants, to the number of emails I received inquiring about the next event and suggestions for where and when (notably, not during Ramadan again), to the guests who were volunteering for a next event (before we even finished with the first one!), my heart is blooming. All this engagement and enthusiasm reflected a strong desire to build community and that many, like me, are searching to belong. So much of who we are as Indonesians, Malaysians, and Singaporeans gets lost in the aggregation of our identities as Asian/Asian American, and surfacing our uniqueness and complexities is something that we crave and evidently need.

Another takeaway is noting the intersectionality of our identities. While this event dipped our toes into exploring one of our identities as Southeast Asian immigrants, acknowledging the further need for specific affinity groups for Southeast Asian immigrants and other intersectionalities (e.g. LGBTQ+; parents; mothers; mixed-race; disabilities; etc.) was something that attendees named. I’m inspired that others have found traction, as I continue hearing about guests who have connected since the event based on other common interests.

Part of the full dinner spread at Mari Kita Makan.

At the end of the night, I noticed a batik tapestry of the three countries from that evening, hanging up at Pasar. “I keep that map to tell people that Indonesia is more than Bali,” Chef Feny explained. It brought me back to the reality of living in Portland, after a night of centering ourselves. The reality that, despite our existence, little is known about us in this part of the world. While many of us thrive, we continue to need to explain our place here in Portland. Finding solace in affinity spaces is critical especially when it becomes easier to disappear in the shadows than to stand out from being different.

The Pasar restaurant team who was behind the scenes of Mari Kita Makan.

Chef Feny Lim (left) and Denise Chin (right) collaborated to bring Mari Kita Makan to life.

Thank you to Chef Feny Lim for creating the evening’s menu and opening up Pasar to host this event.

Pasar is located at 3023 NE Alberta St., Portland, OR.

STORY MAP

A scan of demographics, disparities, and assets.

APANO

BLOG POST

This Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Ecotrust staff who are of Asian descent share readings and writings that resonate with their unique experiences.