Communications Manager

Malia Myers co-founded Landmass Wines with her partner Melaney Schmidt.

In the third interview of a series about Asian American farming, Emilie Chen speaks with Malia Myers, co-founder of Landmass Wines based in Cascade Locks, Ore. Malia shares her journey into winemaking and the inspirations she has drawn from her great-grandparents, who were Filipinx immigrant plantation workers in Hawai’i.

All photos were taken by Emilie Chen, unless noted.

Malia Myers and her partner Melaney Schmidt are both first-generation winemakers. They’re the creators and owners of Landmass Wines, based in Cascade Locks, Ore., nestled in the dramatically scenic Columbia River Gorge. In the short time since Landmass Wines was established in 2018, Malia and Melaney have been able to move into their own winery, acquire their own equipment, and create a safe space for a younger community of wine drinkers, which has been sometimes hard to find as two queer women in a notably rigid, male-dominated industry.

“I could wax poetic on the beauty and magic of wine,” Malia exuded on her passion for her craft. “But basically it’s this agricultural crop that meets in the middle of manual labor, art, and science. It’s wonderfully subjective, while being very much objective… It’s a millennia-old practice, but with crazy, real-world, real-time challenges that are unpredictable. You have to remain flexible, and you can’t have a faint heart.”

My interview with Malia took place over Zoom in late 2023, though I later stopped by their quarterly wine club gathering to take photos and witness the lively community that they’ve created around their brand. Malia grew up in Colorado and Melaney in New Mexico, but they met in Los Angeles, where Malia had been working in the entertainment industry as a production assistant, and later, prop designer.

“I think both of us had gotten as high as we could in our respective careers… We’d maxed out our potential in LA,” Malia explained about the impetus for their move to Oregon. “LA was a great place to get into wine and wine drinking, because you have access to a lot of great wines… But for us, we knew we wanted to be more physical with it.”

On a whim, Malia and Melaney contacted Illahe Vineyards, a winery in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, for a tour. They received not only a glimpse of the winery’s operations but hands-on experience helping to sort grapes. Their one-day visit quickly grew into an invitation by their hosts to stay long term.

“Alright, that’s our chance,” Malia described about their serendipitous offer. “We sold or donated everything of ours in LA and then moved up here in two cars… We camped on the vineyard, woke up to these sprawling hills.”

As with many people of color who are breaking into agricultural and agricultural-related businesses, land access is a significant challenge. “We don’t have the capital to own a vineyard. But we have these really amazing contracts and relationships with growers who are oftentimes retired couples who bought a vineyard and kind of inherited the vineyard management that kind of comes with it,” Malia explained about Landmass’s strategy. “So we started to source [grapes] from different areas. We get Chenin Blanc from down south. We get Grenache from down south. And then we get Tempranillo from the Valley.”

No one in either Malia’s or Melaney’s families, to their knowledge, had previously worked in the wine or beverage industry. “But it is interesting, because my grandfather worked in the sugarcane plantations in Hawai’i,” Malia observed. “He had a very agricultural job. Then here I am, very involved with an agricultural career. “

Malia’s great-grandparents, with their two children, came to Hawai’i from the Philippines in the early 1900s. “That’s early plantation days of Hawai’i,” Malia explained. “At the turn of the 1900s was the really awful American intervention in the Philippines. That history is just absolutely horrendous and really never gets talked about much. What the Americans did at that time in the Philippines was really terrible. So they left to pursue a better life in Hawai’i… at the time, Hawai’i wasn’t a part of the United States.”

“So my grandfather grew up in Hawai’i … I know that my grandpa…didn’t finish third grade, because he was working. This is, you know, the 1910s. There’s some pretty awful stuff about how plantations were run.”

“[My grandmother] came to Hawai’i in the 1920s, because she and my grandfather were pen pals. The introduction was [about] money for the church, and then it became a full-fledged pen pal-ship. Finally she decided that she wanted to marry him—I don’t even know if they had met first. They must have been really great letters!—so he traveled to the Philippines for their wedding, and then they came back to Hawai’i to start their life together“

An older photo of Malia’s grandmother. Photo courtesy of Malia Myers

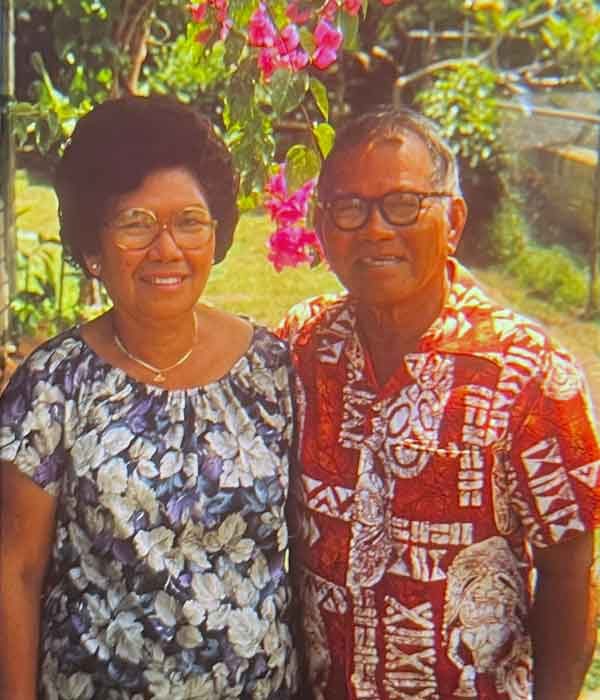

Malia’s grandparents in Hawai’i. Photo courtesy of Malia Myers

Malia’s grandfather eventually worked his way into becoming a mechanic for the sugarcane plantation, before owning a gas station. He later worked as a mechanic for the U.S. military and was present during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Malia’s mother was elementary school-age when Hawaii became a U.S. state. Her father is a “second-, maybe third-generation Kentuckian. Very southern, proper, middle class. His dad owned a grocery store.”

Malia’s mother met Malia’s father when she was 21 and when he was stationed in Hawaii to serve in the Vietnam War. Having grown up in a small island community, Malia’s mother was drawn to the young white man who reminded her of the Beach Boys. After the war, the young couple moved back to Kentucky, where Malia’s father finished medical school, and then went to establish an ER program in Denver, Colo. Ten years into their marriage, they gave birth to Malia’s older brother and, then six years later, to Malia in 1988.

Sharing about her racial and cultural identities, Malia said, “We use a lot of Hawaiian terms for our heritage, which would be hapa… There’s a whole bunch of us hapa kids that come from military and island families. So I feel like that’s the only thing that’s ever felt right… It’s weird saying ‘half Filipino.’ It’s true, but I know much less about Filipino culture than I do about Hawaiian culture. …So hapa feels right.”

“There’s something about [my maternal grandpa] I’ve been drawn to, I don’t know why,” she mused. “[My brother] is what I like to call an ‘indoors guy.’ And I’ve always been an ‘outdoors person,’ just a lot of love for the land, a lot of love for all the animals and the life around me. And so much manual labor… I thrive in operating the machinery, doing the heavy lifting, all the extremely physical stuff. I love it so much. And whether that’s a gene or a personality trait, I’m not quite sure, but I always feel so connected to my grandpa.”

Malia’s parents on their wedding day. Photo courtesy of Malia Myers

Malia’s mother holding Malia as an infant. Photo courtesy of Malia Myers

The wine world is male dominant, with about 4 male wine-makers to every 1 woman wine-maker, and classism and sexism show up in this industry. “[Some people] think that they can get away with things that we know firsthand that they’re not getting away with in our male peers. And that can be incredibly frustrating. …We’ve been in some incredibly misogynistic wineries that have tried everything to just tamp down our spirit.”

But I was so incredibly moved by the determination in Malia’s voice. “We’ve been good at our business and able to get out of really bad situations [which has allowed us to] be more selective with the people that we’re working with… You’ve got to turn that into fuel for success. Honestly, it just has propelled us to move onto the next thing… build a stronger community and persevere.”

“A lot of new wineries want to say that they’re approachable, and what does that really mean? It means being a part of your community and being there when everyone’s going through a hard time. We’re so involved with meeting the people who drink our wine. We know their families, we know their dogs, we know their animals. We love all of them, and we love to be with them.”

Landmass Wines’ quarterly wine club in full swing.

“What does it mean for you to be a winemaker of Asian descent and who is mixed race and queer?” I asked.

“There’s both really amazing things and really unfortunate things about standing out. Sometimes you want to stick out; sometimes you want to blend in. That’s the story of even just growing up when you’re not in the status quo… At times, you just want to be treated like everybody else.”

“You want the same opportunities, you want the same privileges, but at the same time, you’re not part of this homogeneous, monotonous story of other people in the industry. …So you kind of go with it. You’ve got to be true to yourself and make the things you want to make.”

Learn more about Landmass Wines at landmasswines.com.

WEBSITE

BLOG

In the second interview of the Place matters: Asian American farming in the Pacific Northwest series, Emilie Chen speaks with Chantal Wikstrom, who is a granddaughter of Cambodian farmers who came to the US as refugees. Chantal reflects on her childhood growing up on a farm and how that has influenced her interest in one day owning a farm.

Blog

Inspired by the historical contributions of Asian farmers along the West Coast, Communications Manager Emilie Chen explores Asian American farming identity through five interviews.