Communications Coordinator

Elk seen from a trail cam at Yakama Nation Tribal School

Last month, an online class began for a new group of students who are participating in a culturally relevant, mentored, environmental science program at Yakama Nation Tribal School. As part of the Tribal Workforce Development Project, this class connects youth to the urban forests in their communities and aims to inspire the next generation of Native foresters. Here, we reflect on the pilot session of the class, held earlier this spring.

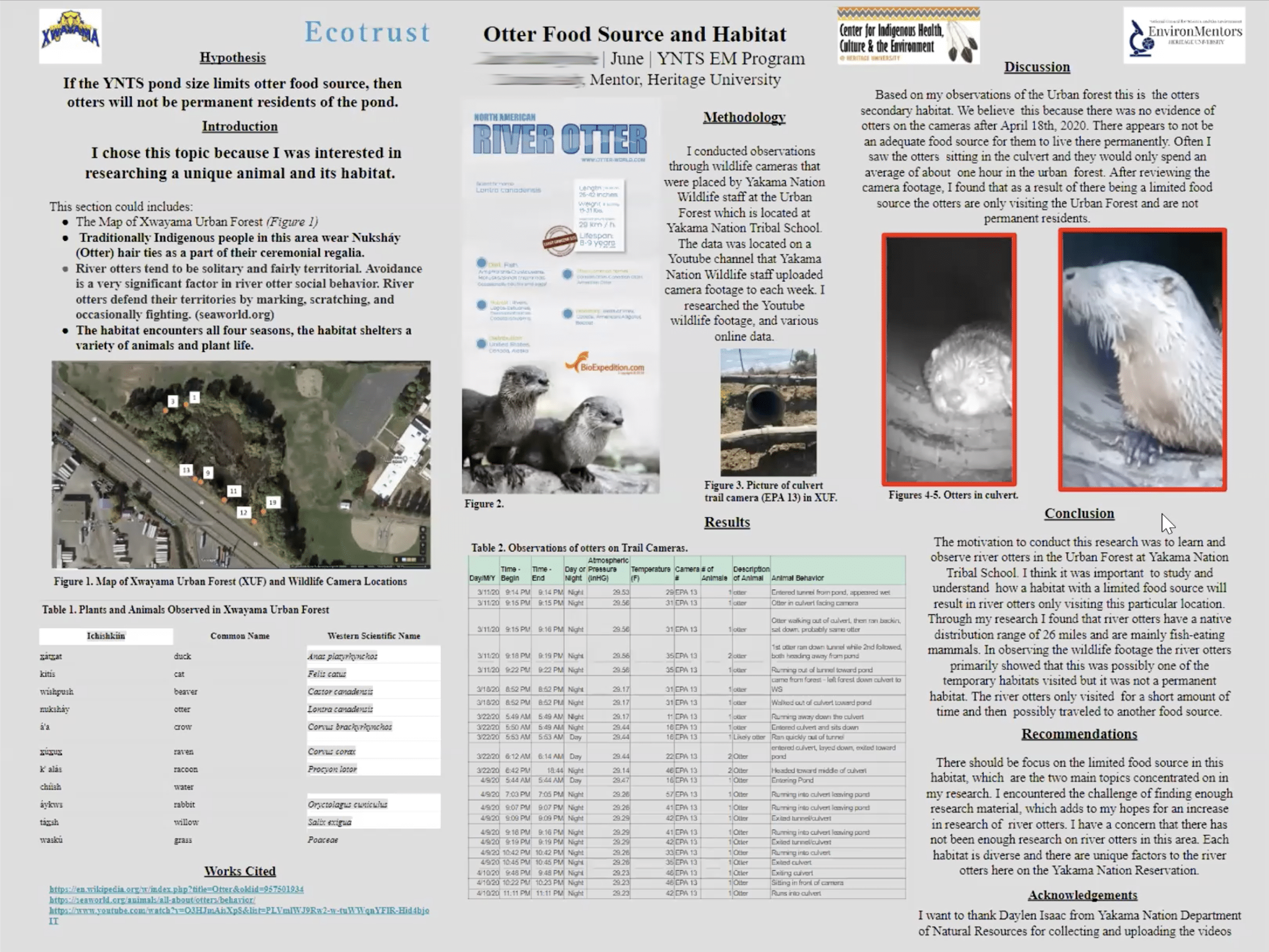

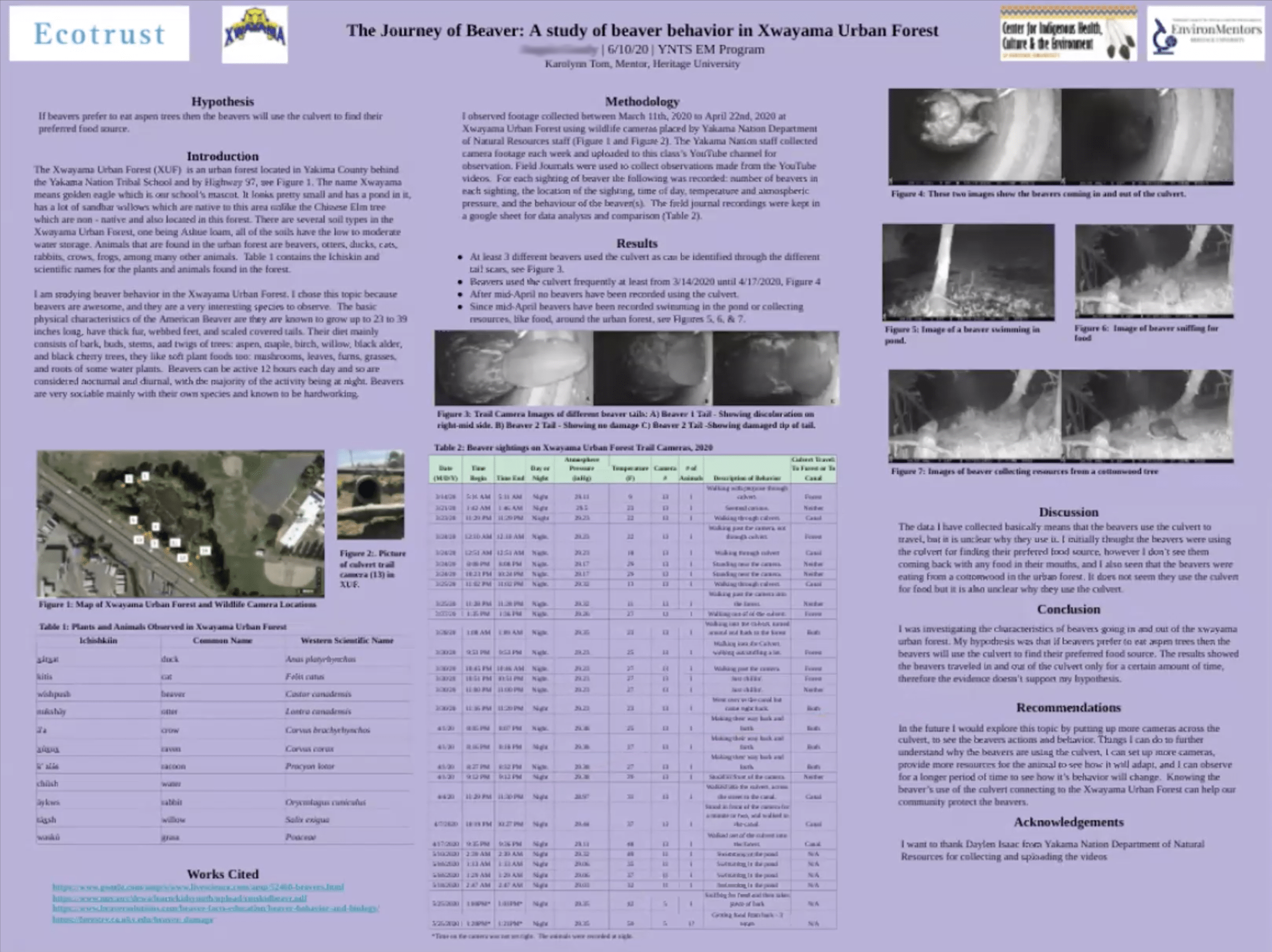

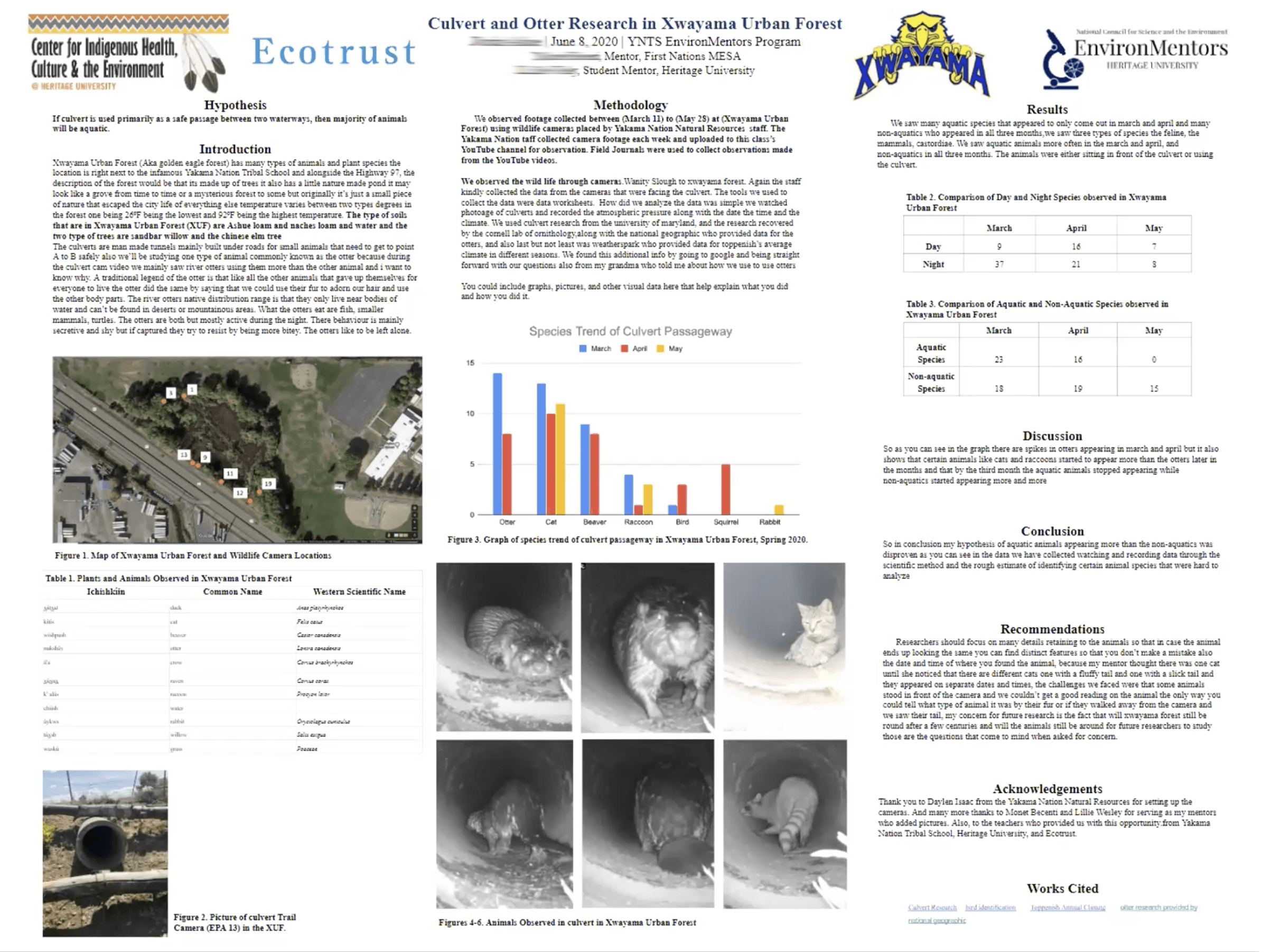

Smooth brown fur, a pair of tiny round ears, and a pudgy snout wreathed in whiskers. An undeniably cute river otter walks out of the darkness of an industrial-looking culvert. This moment, captured on a wildlife trail camera in Xwayama urban forest, was one of many data points observed by students of the nearby Yakama Nation Tribal School. One of the students remarked:

“Based on my observations of [Xwayama], this is the otters’ secondary habitat. [The otters] would spend only about an average of one hour in the urban forest. … the otters are only visiting the urban forest and are not permanent residents.”

This student is one of four students who completed an online environmental science class at Yakama Nation Tribal School earlier this year. Led by Heritage University, this class was structured on the intergenerational mentorship model used by the nationwide EnvironMentors program. Ecotrust’s Tribal Workforce Development Project was asked to support and adapt this class to increase interest and connections among high school students to the urban forests in their communities. With career opportunities in tribal forestry increasing, the Tribal Workforce Development Project addresses an aging workforce by cultivating interest among young people in forestry and providing culturally specific education.

The onset of the pandemic meant the in-person class couldn’t be held as planned, but Jessica Black of Heritage University was determined to keep the class going—online. She reached out to Stephanie Cowherd, our Forest Ecosystem Services Program Associate, who has a background in forestry uniquely complemented by experience in education and communications. Like many educators during this time who must keep students engaged online, Stephanie had to get creative. Murder hornets were the topic of the first class—a perfect introduction to a discussion on invasive species and ecological imbalance.

Eventually, the students were introduced to wildlife trail cams placed around the Xwayama Urban Forest near the tribal school. These data would be the subject of the students’ final research projects.

A satellite-generated aerial photo of a small forest alongside a road. Orange dots are scattered through the forest, labeled by odd numbers from 1-19. Photo courtesy of Yakama Nation Tribal School

Although the instructors were originally unsure whether the trail cams would capture anything, otters, feral cats, raccoons, and more soon began appearing on camera. As the class progressed, the students and their mentors worked together to create a database of the names of these animals—and plants—in IchishkÍin, the Yakama Nation’s native language.

“It was really important for me that the students were able to see their native language side by side with English and Latin scientific names,” Stephanie said. “The IchishkÍin database that the students and mentors added to throughout the program, naming birds, plants, water, and other animals in IchishkÍin, prioritized IchishkÍin names throughout the class and in their final project.”

As Stephanie further explained, plants and animals were first attributed names in indigenous languages. With IchishkÍin words integrated into this curriculum, the students experienced one way that Yakama Nation culture can be centered in science.

Students participating in the class were each paired with mentors, who are college students at Heritage University. “[The mentors’] input is what made the class effective,” Stephanie said about their invaluable feedback and the improvements they contributed to her lesson plans.

The mentors were also compassionately committed to the students’ completion of the class. More than one student described how remembering when it was a class day was challenging while sheltering, and the mentors’ regular communication with students and their families helped keep them on schedule. More importantly, these mentors were also from Yakama Nation, often having community connections with and similar backgrounds as the students. They provided mentorship not just in the context of the class, but also as college students in the next step forward toward a STEM career.

“

I would also like to thank the mentors for sticking with me and helping me throughout this poster… they wouldn’t give up and [would] keep me on track.

—YAKAMA NATION TRIBAL SCHOOL STUDENT

The class convened for two-hour sessions, twice a week, for six weeks. By the sixth week, four students had not only attended the class to completion, but also conducted full research projects, tested hypotheses, collected and analyzed data from hours of trail cam footage, and presented their findings via Zoom.

A research poster by a Yakama Nation Tribal School student

At the end of the class, the students shared that working with the mentors was one of their favorite things about the experience. As the first iteration of this program at Yakama Nation Tribal School, three students expressed interest in participating in the program again.

The program was made possible through the effort of many people.

Jessica Black, Director of the Center for Indigenous Health, Culture & the Environment and Chair of Science Department and Associate Professor of Environmental Science & Studies at Heritage University, led the coordination of the many involved in this class.

Karolynn Tom, CRESCENT Program Coordinator at Heritage University, led a sister program at nearby White Swan High School and was instrumental in the program’s launch at Yakama Nation Tribal School.

Stephanie Gutierrez, in addition to developing the class curriculum, led most classes, calling the pivot to online instruction “a feat” in and of itself.

Teresa Gaddy, our Green Workforce Academy Program Manager, increased the capacity of the whole program, seamlessly stepped in as a substitute mentor or teacher as needed.

The availability of the trail cam data were all thanks to the work of wildlife tech Daylen Isaac, who regularly checked the cameras, downloaded the recorded data, and uploaded it for the students’ viewing.

Adding to the momentum of this work, the US Forest Service has awarded the Tribal Workforce Development Project an additional $100,000 to support the program through the 2020-2021 school year and the exploration of new partnerships and potential pilot programs with other tribes, universities, and natural resource departments. The class is being held again this fall, with all mentors returning, a few new mentors enlisted, and 12 students enrolled.

A research poster by a Yakama Nation Tribal School student

A research poster by a Yakama Nation Tribal School student