Communications Manager

Pam Oja

A conversation with the fourth-generation owner of Tamura Farms, Pam Oja, highlights the experiences of Japanese legacy farmers in Oregon.

Photos were taken by Emilie Chen, unless noted.

The first Japanese immigrants began arriving in the U.S. in the 1860s, though there were initially few. Growing anti-Asian racism from white Americans resulted in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, but the exclusion of Chinese immigrants created a labor shortage along the West Coast. Experiencing famine and wartime conditions in Japan, immigration of Japanese farmers increased during the 1890s to fill this labor gap.

“By the 1910s, nearly two-thirds of all [Japanese] on the West Coast worked on farms.” In California, although Japanese land ownership was less than two percent, Japanese farmers grew more than a third of the produce in the state. In Oregon, by 1909, more than a quarter of the Japanese community worked in agriculture, where they similarly excelled in growing berries, apple, pear, asparagus, celery, and more. In just the Portland area, Japanese farmers were significant contributors to keeping Oregonians fed, with more than 100 grocery stores in Portland stocked Japanese-grown produce (source: JAMO).

The Tamura property as it looks today

Tamura Farms, located in Troutdale, Ore., is one such Japanese-owned farm. On a brisk February afternoon, the fourth-generation owner, Pam Oja (née Tamura), met me on the driveway of the property that her great-grandparents purchased in 1919. Over the past century, the 32-acre property has produced celery, lettuce, cabbage, cauliflower, carrot, and rhubarb at large scale and Asian vegetables like daikon and napa cabbage at smaller scales for individual Asian customers, grocery stores, and community programs.

“Great-grandpa had come over by boat from Japan. But he didn’t have the right paperwork to get into the States, so he jumped ship in Hawai’i. …I don’t know what Great-grandpa did, but he must’ve gotten enough money to get his paperwork, and then he sailed to Seattle,” Pam shared about her paternal family. “He worked in [lumber] for a while. …He brought his wife over, and then he had his [four] kids brought here… They had a restaurant in the Linnton area… Then around 1919, he bought this place.”

Two houses sit at the front of the Tamura property: one that Pam’s father grew up in and another built more recently in the 1960s. A few hundred yards away, an old barn built by her great-grandparents still stands, facing a now grassy area that used to hold a greenhouse.

A retired tractor is stored in the old barn.

Pam describes the pulley elevator system that brought produce up from the barn’s basement, which was used as cold storage.

“Dad would try to seed [the carrots] as thin as he could,” Pam recalled as we passed by a grassy expanse that had not been farmed in some time. “But you couldn’t always get rid of doubles, and so you always had to thin them out. You had to get down on your hands and knees and thin out the carrots… And I can remember having to thin out carrots all day long.” From the age of nine and onwards, Pam had begun helping her mother and aunts with this intensive farm chore.

The successes of early 1900s Japanese farmers drew the ire of white farmers, leading to legislation like the Alien Land Law of 1913 in California, which restricted land ownership by Asians, and Executive Order 9066 during World War II. The latter forcibly relocated people of Japanese descent into concentration camps and dispossessed them of their property and assets. After release, many Japanese then returned to find their homes, businesses, or properties stolen, occupied by others, or unrecoverable.

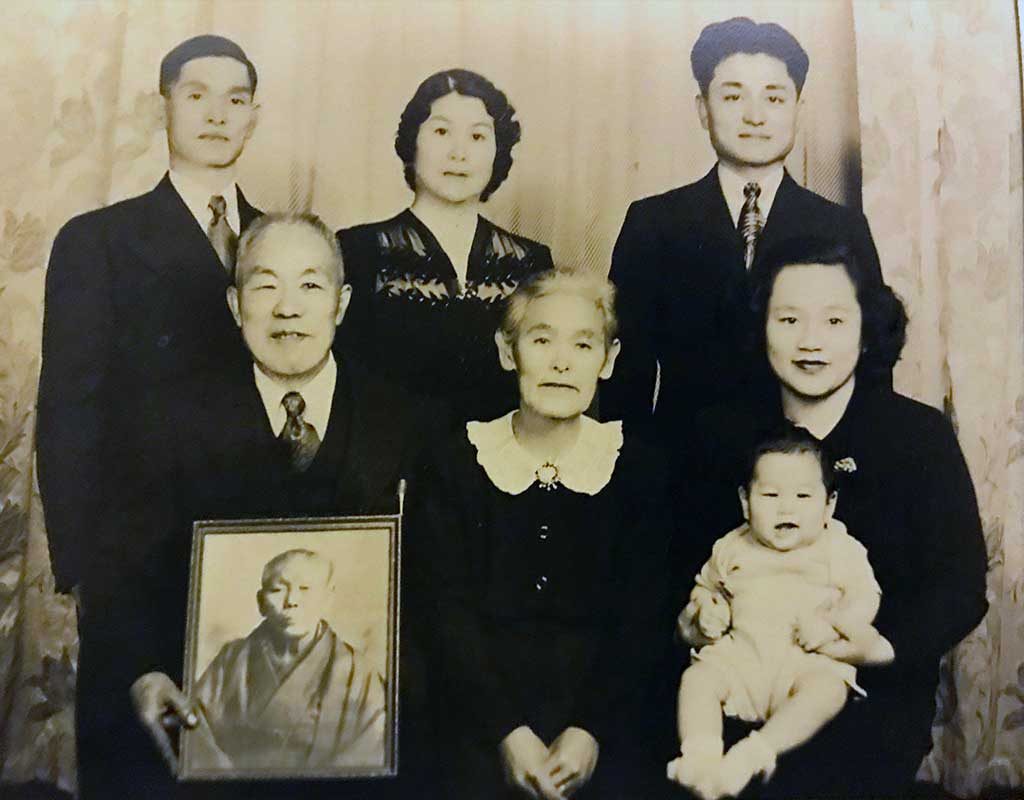

Five generations of the Tamura family. Photo courtesy of Pam Oja.

It is remarkable, then, that more than a hundred years after establishment, Tamura Farms is in Pam’s ownership. “The main farmhouse might’ve burnt down during the war…. That’s why we don’t have any pictures of Dad, because they lost them all during that time. And some things were taken and stuff, but at least they had the farm,” Pam reflected.

As with 2,500 Japanese people in the Portland area, Pam’s paternal family was incarcerated in Minidoka, Idaho. During their three years there, a Filipino family who knew the Tamuras managed the farm on their behalf and returned the property upon the family’s release. “They seemed to have a certain loyalty for [our] family. In fact, I remember them when I was little, they still stayed in contact with them after they got the farm back,” Pam recalled.

Pam’s mother grew up in The Dalles, Ore. where her family owned a cafe, which meant that Pam’s father regularly drove a distance to court her. “Mom grew up in cooking and in serving,” described Pam. Though Pam’s maternal family was incarcerated in Tule Lake in California, Pam’s parents stayed in contact. “It was shortly after that, that Mom and Dad got married in Caldwell [Idaho], right after the war.”

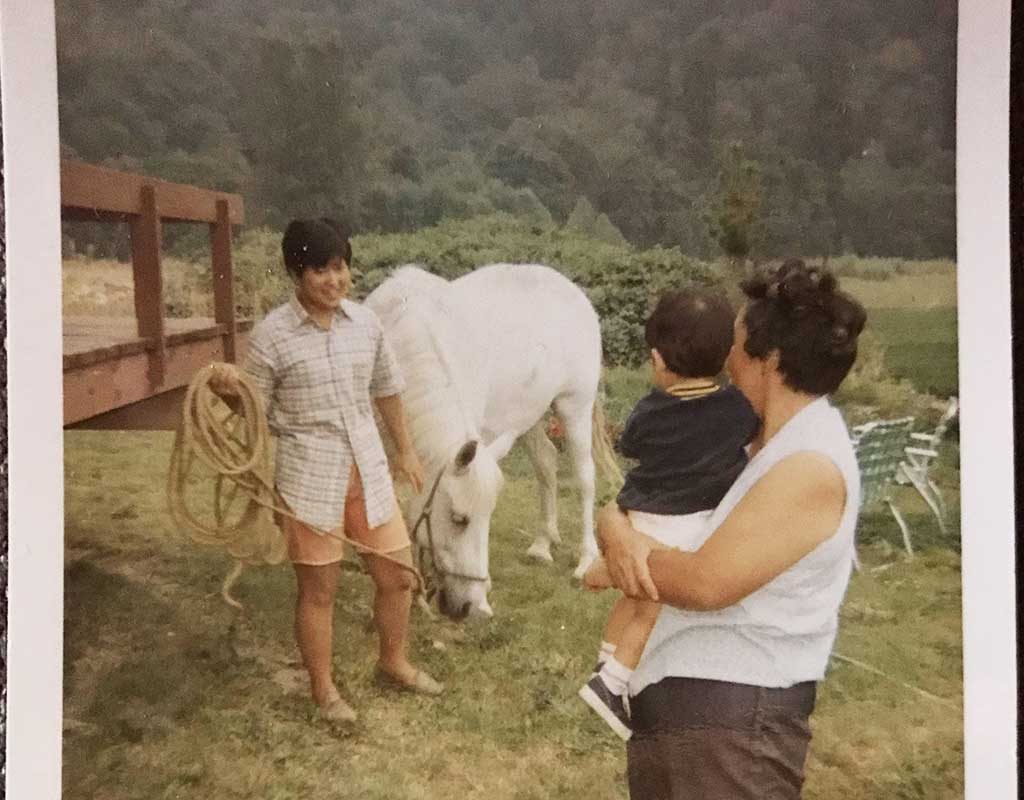

A photo of Pam with her horse, Silky. Photo courtesy of Pam Oja.

Reflecting on her favorite aspects of growing up on a farm, Pam said: “I remember playing with litters of kittens and litters of puppies… Where we grew up in Carver [where Pam’s parents purchased their own farm], we also had dogs and cats too. I had my horse there, and I had always liked horses.”

“When I was young, I had to take piano lessons. And this is how I met my first horse. My piano teacher had two horses at their farm. So whenever [my brother] was taking his piano lessons, I would go down to the barn, and I’d play with those horses. That was probably the only thing that really got me to go to my piano lesson… because I knew I’d be able to see this horse,” she laughed. “This horse was named Silky… And then finally, my piano teacher offered to sell the horse to me.”

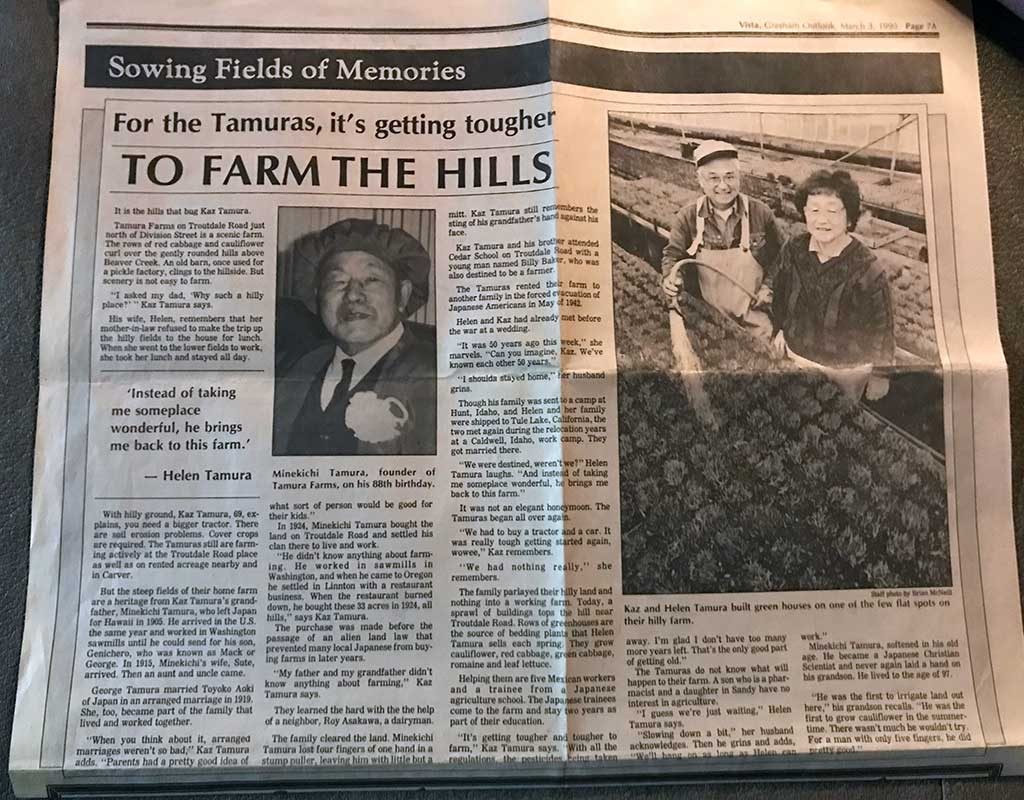

A newspaper clipping from the early 1990s featured the Tamura Farms and its operational challenges. Photo courtesy of Pam Oja.

Neither Pam nor her brother pursued farming as a career. Her brother became a pharmacist, and she taught physical education and coached for eight years, followed by two-plus decades of helping the operations of her husband’s lumber business. But the family farm was still an integral part of her life. She continued assisting her parents with harvesting, deliveries, and payroll of the farm workers, when she was off during the summers of her teaching years or during weekends when she later worked at her husband’s company.

Pam’s parents never truly retired and continued farming for as long as they physically could. When asked about whether they wanted her or her brother to continue the farming legacy, she pondered, “Yeah, I don’t think they would have thought that I’d keep [the farm]. What I really wanted to do was to turn it into a horse farm. …Nowadays it’s just not feasible. The county really has regulations on the barns.”

“People don’t like to pay lots for the fruits and vegetables, you know, not what it’s really worth. I mean, because it’s hard work … and then you sell it for nothing. That’s hard. That’s hard,” Pam emphasized. “That’s why farmers sell [land] to developers because the money is there. And that’s where their compensation is.”

After buying out her brother’s share of the farm property, Pam is now the sole owner of Tamura Farms. She’s been contacted by a local conservation organization interested in buying a section of the property that contains a creek and a large pond, created by Pam’s father. The creek, which has irrigated the farm over the years, is ideal to become a tributary for salmon spawning. The large pond has provided habitat for waterfowl and other wildlife.

While Tamura Farm has not produced on a commercial scale since around the year 2000, Pam has leased sections of the property to other farmers and enterprises, including Catherine Nguyen, owner of Mora Mora Farm, who will be featured later in this series.

“When you meet Asian farmers [from younger generations],” I asked. “Do you have any thoughts on that?”

“I’m glad to see it,” Pam replied. She reflected on the community supported agriculture (CSA) business model that many small, diversified farms like Mora Mora Farm have pursued, “where you can sell one box at a time to people, and they’re willing to pay for it because it’s fresh,” Pam acknowledged. “That is more time-consuming. I don’t know that my family would have been able to do it that way. But farming has changed back to micro-farming. I think it’s a good thing. If I was younger, had more energy, I would be willing to do that.”

Pam stands in front of a field where celery used to be grown, helpfully irrigated by beavers that dammed an adjacent creek.

Ever the animal lover, Pam currently maintains a private barn at her home in Sandy, Ore., where she raises five horses with her husband. “Now I just want to be able to pass on more knowledge and resources to other people or my kids and my grandkids. …Both my daughters ride. In fact, one of the horses I have, I got for the grandkids so that they can ride it. …Because somebody’s got to take care of these horses after I die,” she chuckled.

“What’s your hope for this property?” I asked.

“I hope it stays as a farm,” said Pam. “I hope that the land down below will be saved as a conservancy for the fish, the birds, the deer, the coyotes. Personally, I would like to leave it as land. …I hope it stays natural and also to be able to produce.”

To learn more about the legacy of Japanese farming in Oregon, visit the Japanese American Museum of Oregon.

BLOG

Inspired by the historical contributions of Asian farmers along the West Coast, Communications Manager Emilie Chen explores Asian American farming identity through five interviews.

BLOG

In the second interview of the Place matters: Asian American farming in the Pacific Northwest series, Emilie Chen speaks with Chantal Wikstrom, who is a granddaughter of Cambodian farmers who came to the US as refugees. Chantal reflects on her childhood growing up on a farm and how that has influenced her interest in one day owning a farm.